With 20 straight years of the AK Party regime, especially since the 2011 elections when it received its highest percentage of votes ever (49.9 percent), Erdogan now symbolizes the new chilling trend of strongmen/autocrats across the globe. Grounding his rule in total disregard of the rule of law and institutional checks and balances and driven by his regime’s security, Erdogan has cemented his alignment with a new genre of fascist platforms and sentiments, all of which are rooted in a vulgar nationalist-authoritarian-conservative dogma and morality. After the “failed” coup attempt in 2016, and with the huge help of the new presidential system resulting in his election in June 2018 as the first directly elected executive-president of the republic, the regime has amassed unharnessed power. Moreover, it has sustained a reality-distorting, round-the-clock government campaign that is underpinned by a discourse of hatred against a long list of “enemies” in all spheres of life. Massive arrests, mock trials and purges of thousands of perceived opponents are commonplace under Erdogan’s leadership. Especially since the coup attempt in 2016, which seems to be his “Kristallnacht” in terms of enabling him to deal a final blow to Turkish democracy, Erdogan has stopped giving signals that his is just another “government” under a new presidential system that could be replaced in the future by governments of different shades through democratic politics. On the contrary, the most cataclysmic change caused by the Erdogan’s leadership since 15 July has been to instill the “fear” of his regime’s permanency among the populace.

Renowned scholar Professor Cengiz Aktar’s treatise, The Turkish Malaise, is a timely and poignant search for the root causes of this debacle. A massive part of his answer focuses on revisiting the force of the Ottoman-Turkish past vis-à-vis the West and its relation to the present. But Aktar is fully aware that there are difficult questions framing the complex impact of the empire and the republic on shaping the present regime: first, where do we seek to locate the impact of the past? In policies and institutional behavior? Or in the political thought of the era, generational attachments, values, memory, consciousness, orientations of people – intangibles, in short? Secondly, what about the specificity of each era, contingencies, crises, and global conditions which compel change beyond a historically bound present? How can we deal with the bearings of the past particularly on an Erdogan regime which has been neither coherent nor consistent in terms of discourse and policy since the beginning? Which part of historical consciousness can explain his dramatic reversals?

Aktar considers these questions as part of the same problematic and offers a clear answer: the relations of the past to the authoritarian present can be captured both as ideas/consciousness and institutional/ human behavior. He seeks the presence of the past in today’s changed terrain of culture, judgment and behavior by revisiting the unprecedented historical traumas of Ottoman-Turkish modernization, “the primary and truly compelling dynamic over the last two centuries.” In doing this, Aktar neither glorifies nor demonizes the Ottoman-Turkish modernization process; rather, he explains how the past and present articulate with each other in specific contexts which is especially clear with regard to Erdogan era and Turkey-EU relations.

There is no shortage of consensus on the considerable impact of Ottoman-Turkish political tradition on the present Turkish leader’s understanding of authority, power and freedoms which regards Turkey a country of single, united people; prioritizes national security over constitutional guarantees for fundamental freedoms; defines democracy as the hegemony of electoral majorities not the existence of plural spaces and rights; maintains a “political-military” which has behaved within a culture of impunity; exalts the leadership cult and has always had a media extremely careful not to tread on the toes of power-wielders. However, it is also correct to say that we need to “problematize” the idea that nothing much sets the Erdogan era apart from the rest of Turkish political history and that Erdogan’s is a democratic calamity that was waiting to happen no matter who was in charge. The past has shaped and constrained but not determined the present.

What Prof. Aktar singularly achieves in his thoughtful analysis is to establish the significance of a series of historical traumas in inculcating the hegemonic political orientations of the present. Turkey’s (in)famous nation-building intertwined with its modernization process since the startup of the republic regime in the first quarter of the 20th century based its public philosophy on the ethno-religious cleansing of non-Turks and non-Muslims. To lay the foundations of the secular regime’s legitimacy based on this formula, the public role of Islam was marginalized/delegitimized and the non-Muslim bourgeoisie was annihilated. The Armenian bourgeoisie disappeared in 1915-16 due to genocide and deportation while the Greek community was targeted through killings and population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1922. Aktar points out the violence and hands-on policy of the state elite obsessed with unity and security as the circumstances in which the meta-narrative of the nation is invented. For Prof. Aktar, it is the ethnic and religious fault lines created by a checkered nation-building process as well as massacres of the Ottoman state that have direct bearing on the contemporary Turkish psyche and behavior.

In paying special attention to how the obliteration of populations haunts Turkish minds and behavior, Aktar singles out Armenian genocide as the wellspring from which “contempt for the rule of law, bias in the judicial system, destruction of the sense of justice” are injected into the bloodstream of the nation through acceptance of irresponsibility and impunity of the wrong-doers. The collective amnesia about the unpunished past crimes are a “hidden stigma on the Turkish soul” and have manifested itself as a “weakness on a subconscious level” of all Turks who are programmed to answer a call that awakens their survival instinct in the face of often bogus threats from abroad. What a perfect way to characterize the Erdogan regime whose bellicose nativist-nationalist discourse (yerli ve milli) is essentially rooted in a Muslim Turkish identity that is sprinkled with “beka” (survival) calls against local and international “conspiracies!”

The Character of Popular Support

Prof. Aktar’s writing is also a painful reminder that the nefarious crackdown which “the leader” of the AKP has been spearheading against his self-defined “enemies” receives massive popular support and approval. In fact, one of the most problematic impacts of the genocide as the most open secret truth of Turkish history has been the popular affinity with antidemocratic leaders, Erdogan representing the culmination of a leader with the most autocratic ambitions. A knee-jerk denial of massive human slaughter and dislocation by millions of Turks plays a part in their indifference to violence, injustice, cruelty and suffering imposed by the Erdogan regime. It is true that the denial goes to show how deeply the population is suffused with this hegemonic historiography. But the irony is still there: not being mindful of history and acting as if it is grasped with clarity and full knowledge entail living with its consequences.

Thus, in his cruel and lawless crusade to destroy members of another religious community and pro-democracy dissidents, the Erdogan regime “literally surfs on the predispositions of the social fabric”. It is tragic that Turkey’s left-wing and liberal intellectuals who are still stuck in the simplistic fault line of secular republicanism versus Islamism are also part of the same fabric. Although they oppose Erdogan, they are also strongly against any community that is religious and at the same time visible in public life. The glaring truth is that by keeping silent about the sufferings inflicted on Gülen community members and being vocal on others’, they give Erdogan a free rein in eviscerating freedom, decency, and justice.

In reality, secular republican leaders have historically been compelled to adopt some elements of Islam in politics in order to control and minimize its political appeal. Islamic political platforms have also been tainted by elements of Western cosmology, to which they were supposed to provide alternative responses. Briefly stated, Turkey’s establishment upholds a discourse of secularism that, by not going beyond the “fake” separation of religion from politics, actually depends for its existence on what it denies rather than what it itself is. Perry Anderson captures this link between the rigidity and “intellectual thinness” of Turkish secularism brilliantly when he characterizes secularism as an “ersatz religion in its own right” which “has never been truly secular” even when apparently at fever pitch. Also, in a real sense, the repressive Erdogan regime and Turkey’s secular and (dubiously) “democratic” opposition live the same past traumas and share the same undemocratic foundational dogma that shape the contours of their political imaginations. In the meantime they gloss over the complicated interface of Islam and secularism.

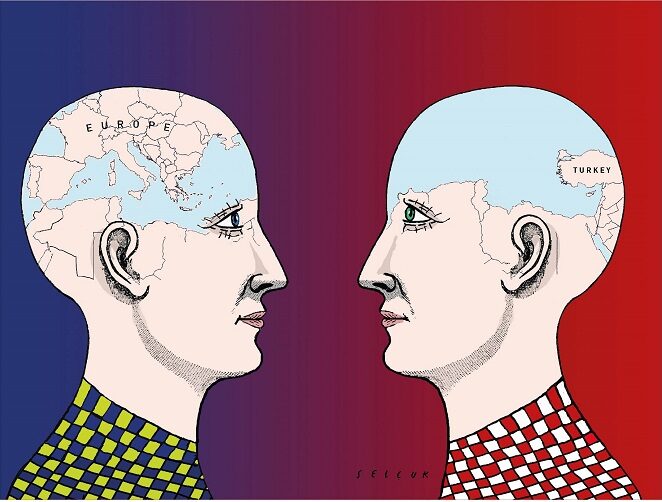

The EU As Part of the Malaise

In explaining the Turkish malaise, as a well-known expert on EU-Turkey relations, Cengiz Aktar assigns special responsibility to the failure of Turkey’s accession process to Europe since 2005 as both a cause and effect of the regime’s sliding toward a full-blown authoritarianism. For him, the integration of Turkey, as “Europe’s other,” could have been the “coronation of a two-century long journey that started early 19th century”, beneficial for both blocs. Believing that the Erdogan governments’ transformative reforms made in line with EU requirements between 2000-2005 changed the face of the country, Prof. Aktar argues that if the process had continued, more and better structured reforms would certainly have prevented the country from sailing away from the shores of the West and plunging into the grim reality of the Erdogan era. It is the abandonment of the integration idea on the part of Erdogan by way of accelerating centralization of power in his presidency as well as the willful orientalist disdain of Turkey by “Christian Democrats of old Europe” who trampled on the process that killed it. However, questions abound about the value of reformist politics: how reliable is the transformative power of reforms in a country where politics has been inhospitable to freedom, equality of citizens, minority rights, constitutionality, the rule of law “historically,” to mention a few basic precepts of democracy? Assuming that reforms are not fragmentary and non-fundamental, this question is also related to how we can make sure that reforms do not lose their central purpose. More significantly, is it true that in attacking the ghosts of the past, reforms can change the social behavior, mindsets, memory and consciousness that are embedded in the entrenched fault lines in contemporary Turkish politics? Buried in the scholarly problem that has compelled Prof. Aktar to pen this essay, there is a fundamental concern that addresses these questions: the task ahead is to refigure the relations of the past to the present to alter their legacy. That being said, Aktar acknowledges that the hold of history on minds and souls supersede the desire to recover from past blemishes. Nevertheless, redemptive politics –as politics of interrogating the Ottoman-Turkish paradigm that frame contemporary politics– is the priority task. That is, if the entity called Turkey wants to do right by democracy.